Wednesday, August 30, 2017

Harvey is a rabbit.

The National Weather Service announced 8/29.2017 that preliminary data indicates the all-time record for total rainfall from a tropical system in the continental U.S. was broken in Cedar Bayou, Texas -- about 30 miles from downtown Houston -- at 51.88 inches.

If confirmed, the record is .12 inches shy of the record for total rainfall from a tropical storm in the entire U.S., including Hawaii and Alaska. The storm, which dropped a foot of rain from Galveston to Beaumont overnight, according to meteorologists, is expected to continue in Texas until Wednesday afternoon.

HOUSTON (AP) - The rains in Cedar Bayou, near Mont Belvieu, Texas, reached 51.88 inches as of 3:30 p.m. That's a record for both Texas and the continental United States, but it doesn't quite pass the 52 inches from tropical cyclone Hiki in Kauai, Hawaii, in 1950 (before Hawaii became a state).

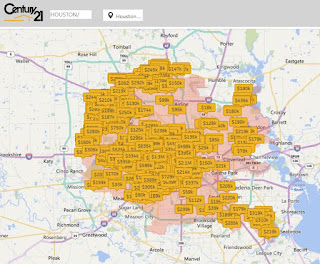

Million Dollar Homes.

The nation’s fourth-largest city is still being inundated by record-setting rain and floodwaters from the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. The National Weather Service has predicted that many areas in and around Houston could total more than 50 inches of rain before the storm ends.

“We are seeing wide spread flooding and this will likely expand and it will likely persist, as it’s slow to recede,” said the National Weather Service. Several fatalities have already been reported, and tens of billions of dollars in damage and loss have already occurred, officials said.

Hurricane Harvey has already dumped 9 trillion gallons of water on Texas and may leave much more before it returns to the Gulf of Mexico. Starting as a category 4 hurricane as it made landfall on Friday night, Harvey has been breaking weather records every hour—and is leaving some scientists wondering why it stalled over south Texas (God’s will) instead of moving cruising northward to Oklahoma and then to the Midwest as storms typically do.

Is climate change to blame for its atypical path of destruction? Well, a bit, according to climate researchers.

Global warming didn’t spawn Harvey it just made him more dangerous. But scientists are careful not to blame all of Harvey’s destruction on greenhouse warming. Houston's lack of rain-sponging green space and devil-may-care zoning laws—have probably made things worse as well.

“Hurricanes are hazards that are exacerbated by climate change,” says Katharine Kayhoe, an atmospheric scientist at Texas Tech. “But the actual risk to Houston is a combination of the hazard—rainfall, storm surge, wind, and vulnerability to the exposure." In Houston's case, vulnerability is particularly high. "It’s a rapidly growing city with vast areas of impervious surfaces," Kayhoe says.

When Hayhoe and others scientists look at the storm itself, they see a hurricane that has been able to keep one foot on the gas pedal while still connected to the gas tank. Warmer water means more water vapor available to power the hurricane, and Harvey’s fuel source—the Gulf of Mexico—is unusually warm right now, thanks to global warming and an unusually hot August in the gulf.

Gulf ocean temperatures are 2.7 to 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit above average. “That provided a deep, warm pool of water used as fuel,” says Dalia Kirschbaum, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who studies hurricane hydrology. Harvey used this hot spot to shift from a tropical depression to a category 4 hurricane in just 48 hours.

In just a decade, the sea surface temperature of the gulf region has risen from 86 to 87 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Michael Mann, a climatologist at Penn State. Mann said that a relationship known as the Clausius-Clapeyron equation tells us there is a roughly 3 percent increase in average atmospheric moisture content for each 0.5 degrees Celsius of warming—almost 1 degree Fahrenheit. That means 3 to 5 percent more moisture in the atmosphere in the Gulf region near the south Texas coast. So Harvey has a bigger tank of tropical moisture that it has been dumping on land.

Over the weekend, Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, looked at the rainfall data from Harvey and did a few calculations on its landfall at Rockport, Texas. He calculated that Rockport would get a foot of rain about once in 1,000 years, based on the average climate of the past 38 years. But taken in the context of the past three years and recent high temperatures, the odds increased to about once in 250 years. For all of southeast Texas, the probability of getting that foot of rain has increased from about once in 100 years to about once in 25 years.

Why the change? First, the Gulf water is warmer. Second, while rainy tropical cyclones like Harvey aren’t more frequent, the high-level winds that usually push them out to sea or north to Oklahoma have stopped blowing.

“We don’t know why the winds have collapsed," says Emanuel, "and it’s too early to connect it to anthropogenic (man caused) climate change." But the effects are clear: the collapse of these winds over south Texas started in 2010 and have remained absent—a time during which Houston has been hit by numerous disastrous storms that have flooded the city.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment